August 26, 2021

Elle Stanger (she/they), or, as she is better known online, The Stripper Writer, has done it all. Sales person, customer service representative, merchandising manager, writer, stripper, cam model, media producer, lobbyist, podcast host, and an AASECT certified sexuality educator — you name it, she’s done it. Stanger has been published naked online since 2005 and when she found herself suddenly unemployed, having just moved to Portland, Oregon, in the middle of an economic recession: “I looked around and saw a bevy of strip clubs. I had serious anxiety and fear around becoming a live, in-person entertainer but it was my best option so I researched some of the clubs online, applied [to] the one that felt more small and intimate to me and ended up working there for 11 years. … I ended up falling in love with stripping.”

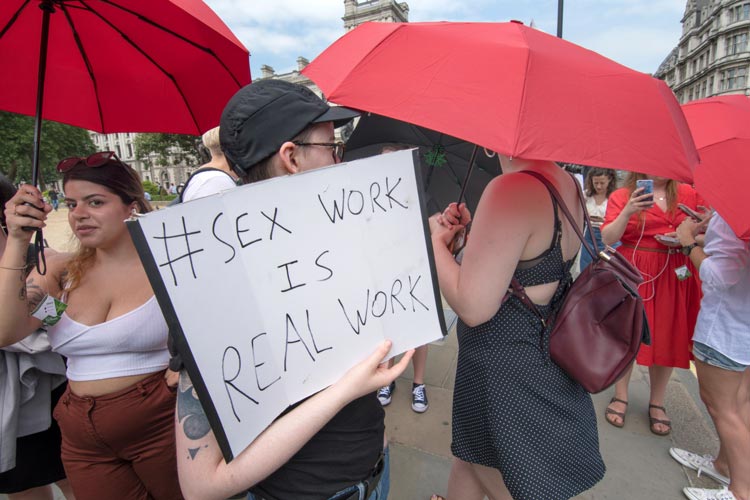

Stanger is a force of nature — one of those people who communicates with effortless transparency, looking not for affirmation, admiration, guidance, or pity — just a mutual respect and openness. Now a long-time resident of Portland, she is a leader of the movement to decriminalize sex work in Oregon. The state recently convened the first ever Sex Worker Human Rights Commission to collate and review evidence based on studies of sex work policy models from around the world. Stanger is one the local Commissioners, also joined by DSW’s Melissa Broudo. There are 11 other members including individuals with lived experience, policy experts, service providers, lawmakers and more.

No stranger to policy work, Stanger is an active advocate in Multnomah County, holding the DA’s office accountable for their promise to stop prosecuting sex workers. In 2014, Stanger helped pass HB 1359 to create a publicly funded hotline offering resources to live entertainers. Entertainers were encouraged to call if they needed legal resources, help filing taxes, or other support. The bill passed but the hotline was only in service for a short time as the state ran out of funding for it. Though it ultimately closed, Stanger still reflects on the experience as “a very successful attempt at showing that we can create resources, not regulations,” for marginalized individuals.

When asked what drew her to this work, Stanger replied, “I have always been a very sexually aware and easily activated person. As a child I touched myself for stress all the time and didn’t understand it. That got me [in] a lot of trouble in preschool.” She describes volunteering in a skilled nursing facility in high school as one of her most formative experiences. “I witnessed people at the end of their lives who weren't receiving the care that they needed — and a lot of fear around death and dying, a lot of social isolation. That was really motivating to me, to realize I only get one life and I only get one body and I don't want to be facing the last of my days with so many regrets because I didn't do things that I wanted.”

At the beginning of Stanger’s career, she worked in an adult novelty store. “I realized that I wanted to know the most I could about sexuality. I watched all kinds of porn, even stuff I didn’t like … I was so fascinated by all the things that people can do with themselves and to each other, even if it surprises me or grosses me out, or confuses me, I just want to know about the world around me. So I read all the books and watched so much porn and tried as many toys as possible and realized I wanted to work through some of my own relational trauma and fear by having more information.”

Within the first few weeks of working at the strip club, Stanger “started to have some of these really insightful, poignant, weird inexplicable experiences with people in the workplace and I wanted to share them.” She had been working as a cam model for many years, running a blog online to publicize her work. The blog had garnered a sizable following, and Stanger began using it to share her stories.“They were there to see me naked [but] would say, ‘You know, I actually really like your stories too.’ They’re either interesting, or they’re sexy, or I’m learning something and so I thought … I guess I’ll just start applying to places and see if I’m any good.”

Thus began their career as a sexuality educator, telling stories of consent, gender identity, pleasure and boundaries. “The feedback and support has been truly immense and there is a huge need for what myself and some of my peers are trying to do,” says Stanger. “I hear from people of all genders and ages. Either I did sex work myself but I never told anyone about it because I was too ashamed; or I am a trafficking survivor or victim who now understands that what I was forced to do is not reflective of everyone’s experience; or I’m a buyer who felt shame about it and now I understand that touch is a human right and this is consensual. I hear from parents who have said that they were really upset and afraid for my child who told me they were stripping or doing webcam so thank you for this article where I can understand that they might be making the best choice for themselves under capitalism.”

Stanger’s ultimate goal is to encourage people to learn and feel good in their bodies, understanding that what people want varies for everyone. “A lot of the harm that happens from sex stems from ignorance and confusion and not from malice,” she says. Stanger helps people to explore these differences in safe and supportive ways. “I don’t strongly identify as a woman — I never have. What grounds me and what interests me is my own desires or fantasies for healthy touch. I really think of myself as a sexual person and allow myself to explore that in a lot of gigs and avenues.” This is what makes her so effective as a sexuality educator: a focus on shifting away from shame and towards openness and information.

Stanger carries this intention into her role as a parent too. “A lot of shame that people carry … is stuff that they learned in childhood, stuff they grew up with, and that can start as early as a kid puts their hands in their pants at the beach, the grocery store, or the classroom and the reaction from the embarrassed, ashamed, afraid adult is that’s bad, and they should stop it. That makes a child potentially feel ashamed of a thing that is normal, but contextually not appropriate.” When her own daughter does things she doesn't understand, Stanger is able to approach learning, not from a place of shame and fear, but information and transparency. Recently, they sat down with their daughter and explained how to have safe sex. “It doesn't shock her that mommy has phalices and models of vulvas around the house. She knows that mommy works with bodies and teaches partly about genitals, so they're just educational models for her. Even that is very outrageous for some people.”

Reflecting on her advocacy experience, Stanger isn’t sure that formal lobbying is for her, although she did train under the guidance of Pac/West Lobby Group and the National Association of Social Workers. One of her biggest takeaways from the experience was the prevalence and impact of stigma against people in live and adult entertainment. Though incredibly disheartening, Stanger was also motivated by the whorephobia she faced. “I have been an out sex worker, porn maker, entertainer, for 16 years now, and as someone who has access to more conventional spaces, I specifically try to train sex therapists and sex educators about the impact of whorephobia. It impacts everybody: people who work in the industry, buy in the industry, have family, friends and lovers in the industry, how we treat people based on where we think they fit in the class system…It’s the stigma that kills people and prevents them from getting what they need.”

Asked about the biggest barrier she has faced to her work, Stanger pauses, “infighting in marginalized communities has been a very surprising and disappointing aspect of in-person and online socialization that I am still learning how to navigate.” She thinks that a lot of this behavior stems from scarcity. “Competition over resources … motivates a lot of harmful behavior amongst people, so I understand how these things arise, but I will say that when I started doing in-person sex work, working in clubs and with other sex workers, you expect and are told that there will be creepy clients — I did not expect infighting or gossiping, or stealing so that is something that can feel very destabilizing when you want to believe in a unity.”

Regardless, Stanger has been able to find community though sex work filed with love and support, but no matter the line of work she’s not convinced any industry is really safe from people weaponizing conflicts or other things against each other, particularly when experiencing hardship. In 2020, Stanger remembers facing the incursion of COVID-19 and “felt this whirring of dread and I thought oh my god it's coming, people are struggling, we’re not going to be our best selves. And I was prepared for that and sure enough I proved myself right. Since the pandemic forced the closing of many venues and competition spiked in online work, defensiveness, fear, and infighting has spiked.” Then, six months ago, Stanger lost her long-term partner to suicide. She shares this information gently, but no less matter-of-factly. “Grief and sexuality is another interesting topic I’m learning a lot about lately.”

Though she loves her job, Stanger is under no impression that sex work is a walk in the park. “I have had to be very tenacious. I think that’s something not a lot of people understand — I was not given any of my current gigs. I worked very, very hard for them and I lost and I failed a lot. But that’s actually something I'm learning is just part of it for a lot of people. Success is to fail.” Stanger was recently diagnosed as autistic, something that makes a lot of sense to her. “I’m really embracing it. It helps me understand my strengths and then some of my weaknesses.”

As our conversation is coming to a close, I ask Stanger if she feels like there is anything I forgot. She doesn’t skip a beat. “Something that’s really important to me is the concept of accountability. As artisan makers, many of us, myself included, have used shared ideas that are ignorant or now outdated when you revisit them 10 years later. So I want to encourage good-faith accountability practices.” For Stanger this means acknowledging mistakes and encouraging accountability without shaming or bullying people. “When I see another creator’s work and I either disagree with it or I’m like, oh we don’t use that word anymore, I look to see when did they write it? What was the context of that piece, do they know better? This is something I’m learning all the time. As someone who has been publishing online for 16 years and started as a nude model blogger, I definitely have said some cringe-worthy stuff.”

Stanger sees this practice as essential to transformative justice, as we continue to try and put our best foot forward as a society in effecting positive change. “People are less likely to learn new information when they’re being shamed. This can apply to anti-vaxxers or in racial education or disability. [With] so many uncomfortable, important topics, if you are telling your audience that they are stupid or dehumanizing them because they don't agree and understand, even if they’re wrong, they are not going to feel compelled to listen to you.” Her writing is the quintessential reflection of this mind-set: unflinchingly honest, funny, and exquisite in its encapsulation of the messiness of the human experience.

To view Stanger’s work visit her website, https://stripperwriter.com/. She can also be found on twitter (@ElleStanger), Instagram (@stripperwriter), and Patreon under the name Strange Bedfellows Podcast.

Courtesy of Elle Stanger.

DSW Newsletter #28 (August/September 2021)

Hero of the Month: Elle Stanger

Sex Worker Human Rights Commission Formed in OR

DSW Staff Advocates at Events Around the Country

Victory in Victoria

OnlyFans Reverses Course

Hero of the Month: Elle Stanger

Hero of the Month: Elle Stanger

Sex Worker Human Rights Commission Formed...

Sex Worker Human Rights Commission Formed...

DSW Staff Advocates at Events Around...

DSW Staff Advocates at Events Around...

Victory in Victoria

Victory in Victoria

OnlyFans Reverses Course

OnlyFans Reverses Course