September 14, 2021

The founders of Backpage.com, Michael Lacy and James Larkin, are being tried in federal court, along with four other employees, for knowingly selling prostitution advertisements on the website. But presiding Judge Susan Brnovich for the U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona declared a mistrial, after the prosecution repeatedly made references to “child sex trafficking,” while none of the defendants have been charged with that crime. Six backpage employees have pled not guilty to facilitating prostitution, while Larkin, Lacy, and two others also stand accused of money laundering.

Before the trial, Judge Brnovich said she would permit the prosecution to present evidence that trafficking had occurred on the site, so long as the prosecution did not focus on the details of the abuse. Brnovich ruled that the repeated lingering on such details by both the prosecution and their witnesses garnered an entirely different “emotional response from people,” and compromised the integrity of the trial. Any trafficking that occurred on the website is devastating, but as the defendants have not been charged with facilitating that crime, the details of its occurrence are irrelevant to the case and may influence the decision.

The federal government initially seized Backpage in April of 2018, following the passage of SESTA/FOSTA, which limited the Communications Decency Act Section 230 protections for internet platforms where advertisements for sex work were listed. The Department of Justice’s announcement of Backpage’s seizure labeled the site, “the Internet’s leading forum for prostitution ads, including ads depicting the prostitution of children.” SESTA was passed with the intention to fight online trafficking by targeting platforms that host commercial sexual content. Anti-trafficking advocates, service providers, as well as law enforcement officers have long been dubious of SESTA achieving its intended outcome. If anything, the law endangers consensual adult sex workers by removing the tools they used to find and screen clients, forcing many workers who used the internet to protect themselves, back onto the streets. SESTA has also been challenged in a federal lawsuit, brought by the Woodhull Freedom Foundation. The lawsuit charges that the law interferes with freedom of speech online. To make the matter worse, law enforcement and service providers also worry that the censoring of major platforms caused by SESTA may have actually increased the risk of trafficking by removing evidence trails that were previously used to detect and prosecute traffickers.

Backpage’s mistrial highlights a critical and increasingly salient issue in the debate over the best policies on sex work: Those who advocate for the criminalization of consensual adult prostitution frequently conflate it with human trafficking. Sex work is delegitimized, and workers are reduced to victims with no agency or voice in their own stories. Not only is this narrative of conflation inaccurate, but it can also be detrimental to the health and safety of communities. Criminalizing sex work does not help address human trafficking. In fact, it misdirects critical resources at enormous cost to those who are being exploited. The prosecution capitalized on this narrative, highlighting only the cases of exploitation on Backpage, and ignoring the consensual commercial exchanges that made up the bulk of its content.

The question of whether or not the defendants did facilitate prostitution remains to be answered. Larkin and Lacy maintain that Backpage used various tools to detect and delete ads for sex. They also argue that any content posted on the site was protected by the first amendment and routinely cooperated with law enforcement to facilitate sex trafficking investigations.

(Jackie Hai, 2021)

DSW Newsletter #29 (October 2021)

Hero of the Month: Kiara St. James

Backpage’s Mistrial

DSW’s J. Leigh Oshiro-Brantly on The Frontier Psychiatrists

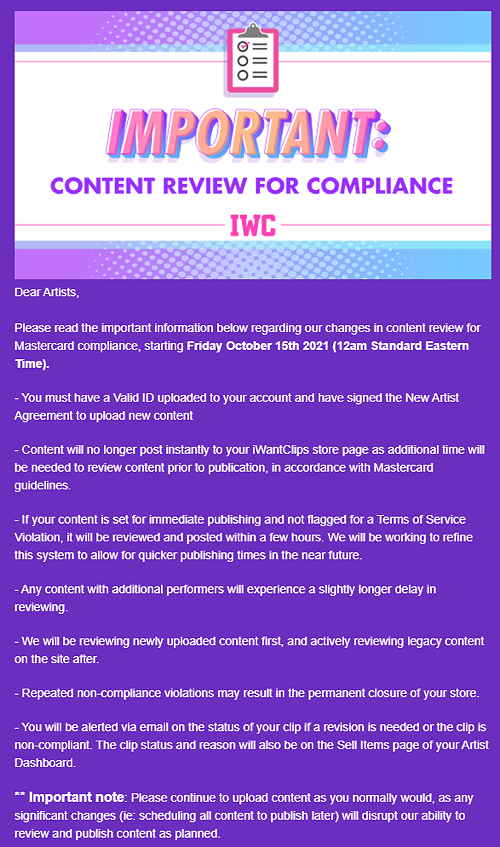

Mastercard Ignores Sex Worker Concerns

Save the Date

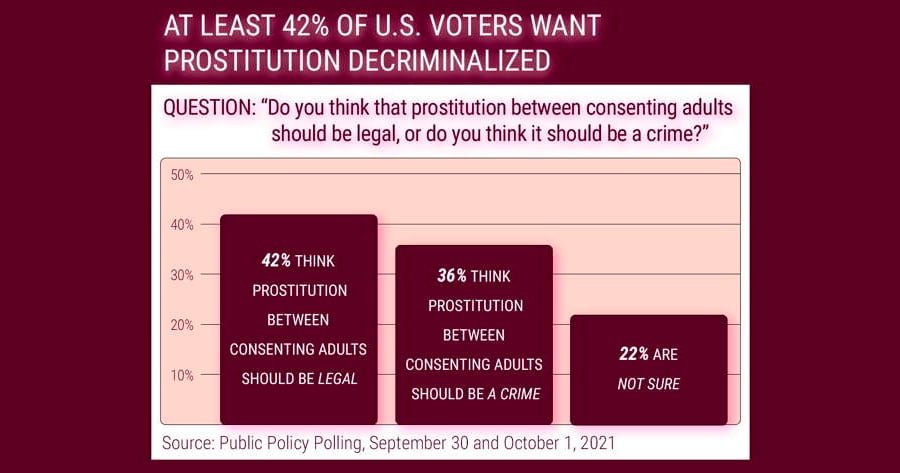

At Least 42% of U.S. Voters Want Prostitution Decriminalized