January 11, 2021

In a 2016 report, Amnesty International called on countries around the world to decriminalize consensual, adult sex work in order to protect the safety, health, and human rights of sex workers, and to combat the egregious abuse and exploitation of human trafficking.1 Numerous other national and international organizations including the World Health Organization, the American Civil Liberties Union, UNAIDS, the Global Alliance Against Trafficking in Women (GAATW), Human Rights Watch, and others have supported that conclusion.2 Human trafficking is a critical issue, not only because of the seriousness of the crime, but also because of its significance in human rights issues more broadly which are “both a cause and a consequence of trafficking in persons.”3

The Freedom Network USA is the nation’s largest coalition working to ensure that trafficked persons have access to justice, safety, and opportunity. Their human rights-based approach to combatting trafficking aligns with DSW’s views on how to end this horrific, exploitative practice.

The Freedom Network USA offers the following guidelines for identifying a person who is being trafficked4:

Human trafficking can happen in any industry, and to persons of any gender, age, and nationality. Stereotypes seen in media are not always representative of real-life situations. However, some common red flags to look out for include:

♦ Person shows signs of abuse, malnourishment, exhaustion, or fearfulness.

♦ Person is not being paid, being paid very little, or is working excessive hours or in dangerous working conditions.

♦ Person is not allowed to leave home or premises or is closely supervised and restricted in movement.

♦ Person does not have access to personal documents such as ID, passport, visa, or social security card.

♦ Person is under 18 and is working in the commercial sex industry.

Again, this list is not comprehensive, and each individual experience is different.

We have a long way to go in the eradication of this grievous crime. The 2020 Trafficking In Persons (TIP) Report made several recommendations for how the U.S. could better address human trafficking. The TIP Report noted that advocates for survivors routinely report a failure of law enforcement to investigate or prioritize labor trafficking. NGOs note insufficient resources dedicated to investigating and prosecuting labor trafficking cases, as opposed to trafficking primarily involving sexual labor, and a lack of familiarity with how forced labor takes place. Indeed, in 2019, 95% of cases opened were investigating trafficking in the sex trade and only five percent were other types of labor trafficking cases.5

Our society’s overemphasis on “sex trafficking” erases and obscures the experiences of so many other survivors of forced labor. This bifurcation can lead to a lack of understanding on how to truly combat the issue, and what trafficking in the sex trade might look like. The Freedom Network USA offers the following definition6:

When a minor (under 18) is given anything in exchange for any sex act OR when an adult (over 18) is trapped or forced into commercial sex by someone else.

Because sex work is generally illegal in the US, sex trafficking victims are often unwilling to seek help and are sometimes refused assistance and protection. Traffickers can be family members, including parents and spouses, friends, and partners. Traffickers often manipulate a person’s isolation, substance use, or dependence, in addition to using violence and threats. Both immigrants and US Citizens are victims of sex trafficking.

It is important to note that victims of trafficking may work alongside individuals who are not being trafficked. They may be working in restaurants, agriculture, factories, or as a 2015 investigation by The New York Times detailed, in nail salons. Traffickers may be parents, spouses, or friends who exploit their victims’ vulnerabilities — immigration status, drug dependence, and social isolation.

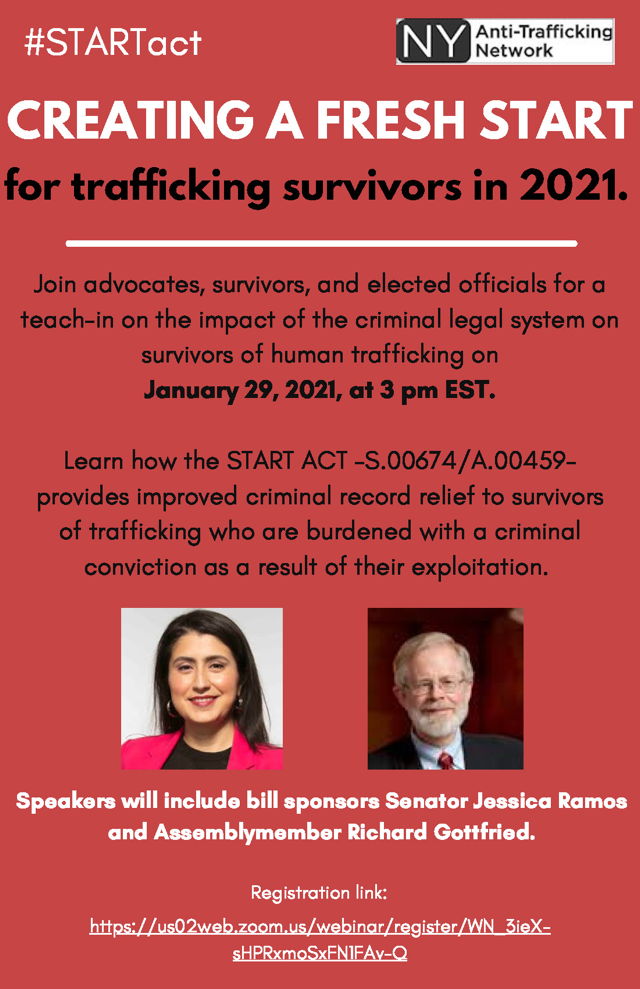

One of the most critical ways to support survivors of trafficking is through restitution and relief bills that allow individuals access to resources to help them restart their lives after exploitation. The US has notably decreased protection efforts, granting fewer trafficking specific visas in 2019, and has failed to adapt federal vacatur laws for any survivor of trafficking who has a criminal record as a result of their exploitation.7 In addition to the decriminalization of consensual, adult sex work, these are critical policy efforts that must be made to protect victims.

As noted by so many human rights organizations, the conflation of consensual adult sex work and human trafficking has lead to detrimental outcomes for both sex workers and victims of trafficking. Where sex work is criminalized, trafficking victims are less likely to be identified or to seek help. The decriminalization of sex work has been shown to reduce the rate of trafficking.

Watch DSW’s video on this important issue here:

If you suspect someone is being trafficked, call Call the National Human Trafficking Hotline at

1-888-373-7888.

If you believe someone is in immediate danger,

please call 9-1-1.

________________________

1 https://www.amnestyusa.org/files/briefing_-_sex_workers_rights_-_embargoed_-_final.pdf

2 https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/decreasing-human-trafficking-through-sex-work-decriminalization/2017-01#:~:text=In%20order%20to%20decrease%20human,the%20full%20decriminalization%20of%20prostitution.&text=By%20removing%20punitive%20laws%20that,thereby%20reducing%20marginalization%20and%20vulnerability.

3 United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking. http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/Traffickingen.pdf. Published 2002:3. Accessed November 18, 2016.

4 https://freedomnetworkusa.org/the-issue/

5 https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020-TIP-Report-Complete-062420-FINAL.pdf, 516

6 https://freedomnetworkusa.org/the-issue/#trafficking-defined

7https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020-TIP-Report-Complete-062420-FINAL.pdf, 516

DSW Newsletter #22 (January 2021)

Hero of the Month: Alex Andrews

Washtenaw County Decriminalizes Consensual Sex Work

January Is Human Trafficking Awareness Month

DSW Staff Share Their Expertise

Mark Your Calendars for January 29

Hero of the Month: Alex Andrews

Hero of the Month: Alex Andrews

Washtenaw County Decriminalizes Consensual Sex Work

Washtenaw County Decriminalizes Consensual Sex Work

January Is Human Trafficking Awareness Month

January Is Human Trafficking Awareness Month

DSW Staff Share Their Expertise

DSW Staff Share Their Expertise

Mark Your Calendars for January 29

Mark Your Calendars for January 29