December 21, 2021

After more than a decade of commitment to harm reduction in transgender, sex worker, and housing rights spaces, Joaquin Remora has never lost his sense of curiosity about his community. “I understood very early … that these dynamics, people living on the streets, are entirely misunderstood. To do this work I needed to have curiosity rather than an opinion. Like, hey, what’s your story? What do you need?” Now the Director of Our Trans Home SF, a coalition of organizations addressing housing instability for Transgender, Gender Variant, and Intersex (TGI) people in the Bay Area, Remora has channeled his open-minded, dynamic nature into building the city’s first transitional housing program for homeless Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming (TGNC) adults.

Remora initially moved to San Francisco from Vancouver, Canada, looking for a community in which he would feel comfortable transitioning. He joined St. James Infirmary, the first occupational health and safety organization for sex workers in the country, and a parent organization of Our Trans Home, as a participant. Remora’s care for his community and expertise was quickly recognized and he was asked to join St. James’s board of directors. Our Trans Home was founded in January of 2020 and Remora began to volunteer. When it became apparent that the program needed strong trans leadership to succeed, he stepped in as director.

Navigating enormous obstacles, of which COVID-19 has only been one, Our Trans Home has flourished with the support of Remora and other transgender leaders, now serving about 150 participants. But this is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to need. Remora had previously worked at a housing navigation center, gaining expertise on the risks and challenges posed by housing programs, particularly for TGI community members. The San Francisco shelter system is built on a temporary housing model, ill-equipped to provide any kind of long-term resources to the communities they serve. Many unhoused trans folks end up leaving the system because they don’t feel safe. Funding, says Remora, is the biggest challenge.

Born on the western peninsula of Mexico, Remora was raised near Vancouver, BC. He was drawn to the richness and diversity of the culture in San Francisco, something that he felt was missing in Vancouver. Remora describes growing up “in a very specific way that made the bigger picture very clear. Whereas maybe if I had been raised in a more progressive home or my parents had been liberals, or if I wasn’t mixed-race, maybe anything like this would have not made everything stand out so stark[ly] to me.” He also points to the different cultural cues he received from his father’s spiritual indigenous family and his mother’s more material white one providing a great deal of insight about his own journey: “Understanding the systems and the way they impact people emotionally and spiritually, and seeing that you can have a lot of very dysfunctional behaviors due to the trauma that you deal with. But you can be more in touch with your humanity that way [than] someone who is aligned with the system and has access to more resources and yet there is so much more suffering and detachment.”

While living in Vancouver, Remora began doing harm reduction with the unhoused population there. He was also working at the BC Compassion Club Society, the oldest and largest medical cannabis dispensary in Canada which is completely consensus-based and run by indigenous women. Vancouver is also home to North America’s first safe injection and needle exchange facility and a lot of harm reduction policy innovations. After working as a service provider for so long, Remora took an enormous risk, moving to San Francisco without documentation, money, or permission to work legally. He was dealing with his own substance use and beginning to transition and relied a lot on St. James for resources and community until his life stabilized and he once again became a provider.

In part because of his full-circle perspective, Remora doesn't identify as an activist, but rather an advocate or a friend to community and sex workers. While his advocacy has blossomed into a career, for Remora that was never the point. “I don't want to identify the work as separate from my own path. … For me, this is just how life should be. These things are a part of my story and therefore this is just what comes with showing up to that story and telling [it] so that things can improve for anyone in that situation. I want to normalize it.”

Remora sees relationship-building as central to his work: getting to know people, understanding their unique stories, struggles, and trauma, and helping them achieve their goals with appropriate support. It’s far from perfect, but seeing people build up their self-esteem and become more and more themselves every day, simply by having access to basic resources is incredibly rewarding to him. “There is so much gratitude,” Remora says. “I don’t ask for any gratitude because housing is a human right. But … when you go from having nothing to feeling like a normal part of the world, that is a really generous place of gratitude.”

Reflecting on the most significant challenges he has faced, Remora pauses. “There is still so much that society at large doesn’t understand about trans people — the city doesn’t understand that they are not going to stay in their resources because it’s not safe for them.” Remora says he too is learning every day, about transmisogyny and other invisibilized forms of violence. When asked if he ever feels like he’s trying to put a band-aid on a bullet hole, Remora laughs. “Definitely. But I’m lucky that I have some really radical mentors that are like, ‘We can’t really put too much weight on this because it’s kind of shoveling water.’”

Remora also reframes the work — away from solving the problems themselves, and towards setting up systems and solutions that allow people with lived experience to lead. “There are little ways in which I’m not looking at this as a solution. I’m just saying let’s just put those problems in the right hands, more than anything.” He feels fortunate to have strong mentors who are uncompromising in their dedication to taking action based on consensus and setting up strong boundaries.

Looking forward, Remora hopes that the success of Our Trans Home will be a jumping-off point for other programming. He is optimistic that the city will agree to help fund a navigation center for a specifically trans and TGNC shelter system focused on serving people of color. He also hopes to budget for trans and TGNC staff, who already donate so much of their time to this work. Again the need is enormous: they need services for people living on the street who aren't yet ready to transition to permanent housing, better mental health services, access to healthcare, and employment development. “Right now we just need to demonstrate to funders how well our program is working and how much more it needs to grow to make a difference in the larger population.” He also hopes that the organization can develop direct referrals for asylum seekers and programs supporting migrant sex workers in order to get trans people out of detention centers faster, referencing a detention center in New Mexico with 60 trans women from Central America seeking asylum.

Remora is forever staying attuned to how the movement can heal its own trauma, build solidarity, and take collective action to challenge systemic violence. “It requires everyone to do a lot of healing and self-exploration, deprogramming from the things that keep us separate, and being curious about each other’s cultures. Because that’s what’s going to help us be stronger together.” He sees what they are up against as rooted in centuries-old systems of oppression. “To look at another person and say ‘you’re not human,’ that comes from a very injured place. Transphobia and whorephobia are the same thing … to me, it’s a spiritual disease that’s the issue and how do we help each other do that healing and that deprogramming?”

For Remora the answer is simple — through, curiosity, and love. “There’s a lot of things that cause harm to the movement … understanding what love really is and what it isn’t. This work comes from a place of love but if you are confused about what love means we’re not going to be able to make the right moves. To me, the lesson is really defining one’s philosophy of what love is, love for the community, love for all humans. That’s always the thing that re-centers me. Because that’s love, Instead of saying, well I suffered, now I’m gonna get my piece of the pie, no I’m gonna remember that I suffered so other people don’t have to.”

(Courtesy of Joaquin Remora, 2021)

DSW Newsletter #31 (December 2021)

Burlington, VT City Council Votes To Remove Language on Sex Work From Its City Charter

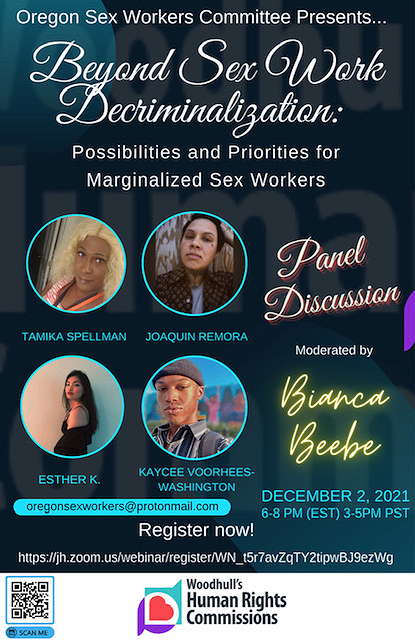

Johns Hopkins University Hosts Panel on Decriminalization

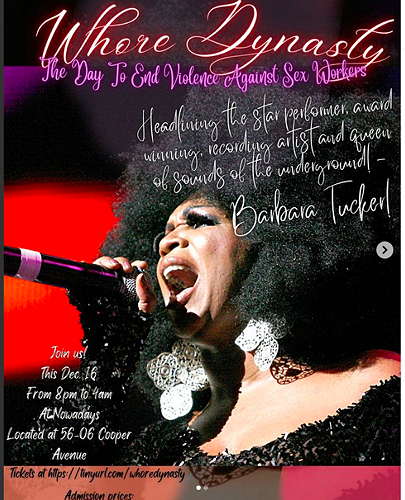

Honoring International Day To End Violence Against Sex Workers

Hero of the Month: Joaquin Remora