July 31, 2024

The New York Times recently published an article that sheds light on the severe impact of deepfake pornography on its victims. This form of digital abuse involves AI-generated images or videos that alter a person’s likeness to create realistic but fabricated explicit content. While deepfake pornography can target anyone, it often disproportionately affects women, particularly those in the public eye such as celebrities, politicians, and influencers. As AI technology increasingly integrates into various aspects of our lives, it raises significant ethical questions. However, the challenge legislators face is how to address AI-generated content when it crosses the line into criminality.

The New York Times piece features the stories of two female politicians in Florida who were targeted by deepfake pornography seemingly to retaliate against their policies or the fact that they were women in positions of power. Sabrina Javellana, a city commissioner in Hallandale Beach, and Democratic Florida state senator Lauren Book, were both victims of deepfake pornography. Javellana, in the wake of the abuse, felt that she had little recourse to deal with the images proliferating online. In response, Senator Book introduced Senate Bill 1798 to address pornographic deepfakes online.

According to the article, “Gov. Ron DeSantis signed S.B. 1798 into law on June 24, 2022. At the time, four other states — Virginia, Hawaii, California and Texas — had enacted laws against the dissemination of deepfakes. Floridians would be protected against deepfake abuse — ostensibly, at least. Now that circulating such images was explicitly criminalized, the F.D.L.E. and local law enforcement could investigate victims’ claims. Those who circulate deepfakes could be charged, fined and possibly jailed. Victims could now pursue civil suits as well. Legislative solutions like this are an important step toward preventing nightmares like Javellana’s; they offer victims possible financial compensation and a sense of justice, while signaling that there will be consequences for creating non-consensual sexual imagery.”

Congress has taken action to address deepfake pornography. In January, they introduced the Disrupt Explicit Forged Images and Non-Consensual Edits Act of 2024 (DEFIANCE Act), a promising piece of legislation aimed at providing victims with tangible recourse. If enacted, the bill would allow those affected to claim $150,000 in damages and seek temporary restraining orders against perpetrators. This legal step represents a crucial move towards acknowledging the severity of deepfake pornography and offering support to its victims. However, while such measures are essential, they also bring to the forefront a complex issue: the role of online platforms and their responsibilities in curbing this type of abuse.

Carrie Goldberg, Javellana’s attorney, argues that platforms won’t be incentivized to remove deepfake images unless Section 230 of the U.S. Communications Decency Act is amended to make them liable for non-consensual content posted on their sites. The Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA) and Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA), signed into law in 2018, amend Section 230 by suspending its protection in cases where online platforms are perceived to be promoting prostitution. Rather than preventing the online exploitation of trafficked persons, these laws have hurt the people they intended to help, pushing sex workers and trafficking victims into more dangerous and exploitative situations. FOSTA/SESTA serves as a stark reminder of the unintended consequences that can arise from efforts to regulate online content. This outcome underscores the importance of including sex workers in the legislative process to ensure that their perspectives and needs are considered, preventing policies that inadvertently harm those they intend to protect.

Victims of deepfake pornography deserve justice and protection, and legislative measures like the DEFIANCE Act are a step in the right direction. Yet, we must also be cautious about the broader implications of altering Section 230 and the potential for increased internet censorship. The focus should be on developing targeted solutions that address the specific harm of deepfake pornography without infringing on free speech, censoring the internet, and harming sex workers in the process.

DSW Newsletter #55 (Summer 2024)

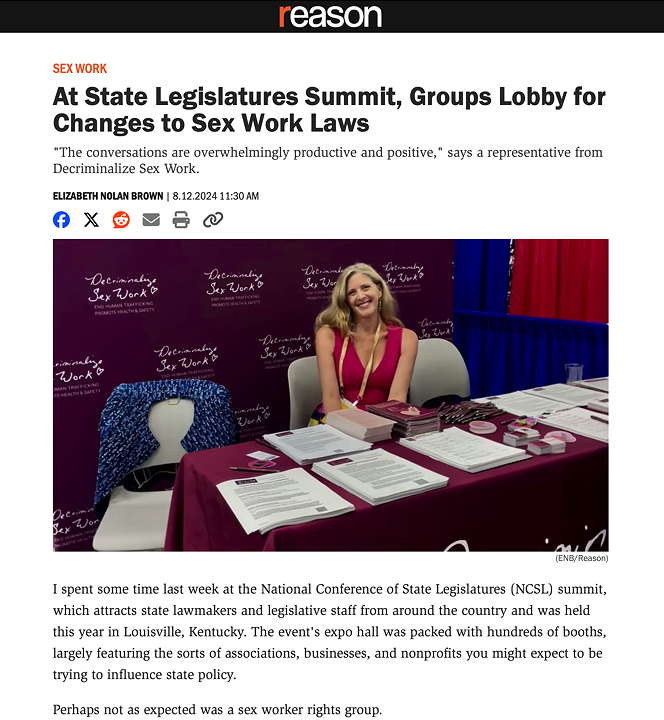

DSW Attends FreedomFest in Las Vegas and NCSL in Louisville

VT Advocates in Action

DSW in the News

The New York Times Covers Deepfake Pornography